BY KELLY EGAN, OTTAWA CITIZEN

BY KELLY EGAN, OTTAWA CITIZEN

OTTAWA — Memory may be what you hold, but remembrance is what you do — the past dusted clean, made to breathe again.

It is a Dutch woman, blond, soft-eyed, visiting the cemetery where her parents are buried in western Holland and seeing a single headstone for a Canadian soldier, strangely separated from the military graveyard, and wondering: Who and how? And not just wondering, but asking, acting, warming the story on a cold headstone.

In 2002, this launched Alice van Bekkum on a mission. She, indeed, found out who the soldier was, this Harold Magnusson, even visited his family in New Brunswick in 2011. She also dove into the story of eight other members of his unit, the 23rd Field Company of the Royal Canadian Engineers, who had died close to where she lived, almost all on the same night.

They perished in September 1944 in the aftermath of Operation Market Garden, a failed effort that forced a frantic evacuation of Allied soldiers caught behind German lines. She had even met a pair of local men who, as 11-year-olds, had hauled Magnusson’s body out of the river.But one name, one mystery from the 23rd FC, stood out. Lance Cpl. Antonio Barbaro, only 22, who died in February 1945, months later than his fallen mates. Why? How? She just had to know. “If we never mention their names,” she wrote this week, “they have died in vain. We’ll remember them here. I hope you’ll remember him in his hometown.”She enlisted a Canadian accomplice or two. Soon, she had Lance Cpl. Barbaro’s military records, pulled from archives. There was an appeal to the Citizen. The pieces began to come together.

Forgotten, he is not. He has a niece and nephew in town and the odd Village old-timer remembers the Barbaro family, which included brother Dominic, or “Lefty”, a once famous southpaw on the city’s ball diamonds.

Antonio Barbaro, who wanted to be called Tony or Anthony, was the youngest of eight children, born in July 1923. His father, Pasquale, was a street-sweeper for the city, mother Catherine was short and stout, and ran the roost, a boxy house on Norman Street, only steps off Preston, with a giant kitchen. She barely spoke a word of English.They were, of course, Roman Catholic.

Anthony attended about three years of high school at Ottawa Tech, enlisted when he was 19. He played trumpet in a youth band that practised at St. Anthony’s, liked to draw and paint, often had a smile on his round face. He had trained to be a draftsman.

According to his war records, he was not a big man: 5-7, about 155 pounds at sign-up, with brown hair and eyes. He had 20/20 vision, was in good health, was missing his tonsils. When he died, he owned a wrist watch, a Ronson lighter, a few other effects. He never married.

He was among a group of Canadians who helped evacuate about 2,500 British paratroopers by ferrying them across the Rhine River, near Arnhem, under heavy shelling. Some of the rescuers made up to 15 trips in the dark, during a night of terrible weather, in so-called storm boats equipped with 50-horsepower motors.

He was mentioned in dispatches. “Also outstanding in this operation were Tony Barbaro of Ottawa and Sapper Raymond Lebouthillier of Ste. Bernadette, Que.,” reads a 1944 story from The Canadian Press correspondent travelling with the army in Holland.

It was dangerous work, some of the boats being blown right out of the water. Operation Market Garden was a daring idea, and the failure and rescue were dramatic enough to be adapted for screen in the movie A Bridge Too Far.It was a boat, ironically, and a river that led to Barbaro’s demise.

In February 1945, he and two other members of the 23rd field company launched a small boat into the Maas River near a strategic bridge in Mook, in mid-eastern Holland. As they attempted to attach a rope to a boom that needed work, the bow of the boat struck something sharp on the boom, slicing the hull open.

There were only two life-jackets. Barbaro insisted the two non-swimmers take them and he would fend for himself. At least 60 yards from shore and dealing with a heavy current, he tried to swim. One can only imagine the temperature of the water in February and the weight of his boots and uniform. A witness saw him sink; the other two were rescued.

There followed a touching letter to his mother from the unit’s padre. “You see, dear Madame,” he wrote to Catherine, “you have many reasons to be proud of your son. He sacrificed his life to give to his companions a better chance to live.”

Anthony, he added, had been to mass and confession the Sunday before he died. “The war seems to take the best among us … I dare say that he was one of the best of my flock.”

Sad, too, that the war was nearly over. Barbaro would not see his 23rd birthday. He is buried in the Canadian Military Cemetery just outside Nijmegen in Holland.

All of Anthony’s siblings are dead, but he has a nephew, named for him, a Tony Barbaro, now 65, who lives in Richmond, retired after a 31-year career in the RCMP. (His father, Sam, also served in the forces.)

He spent many hours at his grandparents’ house on Norman and remembers big, raucous meals with 30 at the table. But the subject of Anthony, the baby of the family who left at 19 and never came home, was off limits.

“They didn’t talk about it,” he said this week. “If you brought it up with my Dad, he’d walk out of the room.”

His grandparents were very big on their children becoming wholly Canadian, not hyphenated ones with one foot in the home country, he said. So Antonio became Tony, Salvatore became Sam, Pasquale was Pat.

He has not been to his uncle’s grave but is touched to know that someone like Alice is doing her best to keep the story alive.

“I think it’s wonderful,” he said. “It’s nice to know that they appreciate it. Because it was a big deal for my family. You have to know them, and if you knew them, you’d know why.”

(The family has so little information about Anthony, in fact, that they couldn’t track down a photo. But the irrepressible Sal Pantalone, an amateur historian close to 90, was able to find one in his files. He remembers the Barbaros fondly and was a band-mate of Anthony’s in the 1930s.)

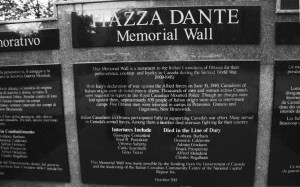

Anthony Barbaro’s name is etched in granite in a little square below St. Anthony’s Church, among six Italian Canadians from Ottawa who died in service during the Second World War. Next to it are six names of local Italians who were interned, for suspicion of treason — these were complicated times.

Van Bekkum, meanwhile, attends Remembrance Day ceremonies every year. She has placed a New Brunswick flag and a painted stone at Magnusson’s grave. She would like, possibly, to lay a wreath from Ottawa in Barbaro’s name at the 70th anniversary of Operation Market Garden, subsequent Operation Berlin, in 2014.

“Young Allied soldiers did not ‘give’ their lives, like so many say,” she wrote. “But, far away from home and family, it was taken from them by the enemy.”

Yes, Alice van Bekkum, faraway stranger, it was.

The rest falls to us, the lucky ones, to make real this thing called “honour” — by what we say, but mostly by what we do.

To contact Kelly Egan, please call 613-726-5896, or email kegan@ottawacitizen.com twitter.com/kellyegancolumn

© Copyright (c) The Ottawa Citizen