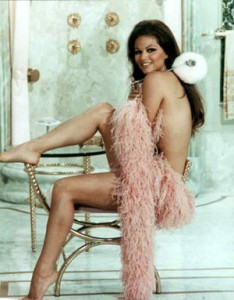

1. Claudia Cardinale

1. Claudia Cardinale

Some might say Loren, some Lollobrigida, some Bellucci, but of all the Italian screen goddesses who dominated postwar western cinema, it was Ms Cardinale

who took the Garibaldi. Equally ravishing when tousled (The Professionals), or tightly coiffed (The Leopard), playing bosomy peasant girl (Cartouche), or leggy trapeze artiste(The Magnificent Showman), she glowed, pouted, teased and always looked indefinably, sparkly on-for-it. Her kohl-drenched eyes flashed.Her smile dazzled. “If you ask me,” said David Niven, “Claudia Cardinale is, after spaghetti, Italy’s happiest invention.” Quite.

2. Il dolce far niente

Or “the sweet doing nothing.” Pleasant and carefree idleness. Delicious laziness. Taking it easy as an existentialist statement. Italians have somehow managed to patent this exhortation to chill out, kick back and don’t get hung up on work or on the pursuit of fame and fortune. Not to be confused with the Latin carpe diem, which preaches the exact opposite. Or with La Dolce Vita (“the sweet life”) a film in which playboy paparazzo Marcello Mastroianni spends three hours frantically racing from party to party in pursuit of voluptuous birdbrain Anita Ekberg.

3. Cars

How do they do it? What is the mystical connection between Italian engineers and the automobile? They were in at the start, with the invention of the Barsanti-Matteucci

internal combustion engine in 1860. The small-but-whizzy car was invented by Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino in 1899 (although Fiat later became the alleged

acronym of “Fix It Again, Toni.”) Since then, Lancia, Bugatti, Alfa R o m e o, Lamborghini, Maser- ati and pre-eminently Ferrari have set the gold s t a n - dard of car design ? a

combina- tion of sleekly beautiful lines and sublime attention to detail. In 1925 the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio compared the Fiat 509 to a beautiful woman for its grace, slenderness and its ability “to pass with ease every roughness.” In 1999, Jeremy Clarkson rhapsodised for 20 minutes on the perfection of the Ferrari’s gear-knob. Italian cars make grown men sigh and weep.

4. Gondoliers

Straw-hatted, stripy-vested, red-kerchiefed and indefinably louche, the Venetian hybrid of taxi driver and ad hoc crooner has proved irresistible to visitors for 900 years. Though their rowing motion suggests a kitchen scullion stirring the contents of a giant cauldron, these men embody the soul of Italy, as they ferry supine romantics down the

Grand Canal in black-painted, 35ft-long floating coffins, and sing “O Sole Mio” and “That’s Amore” at them for fares of up to ?175 an hour. The city’s 425 male gondoliers were finally joined by a (sola mia) female, Giorgia Boscolo, in August 2010.

5. The sonnet

The 14-line, strictly rhyming poem so loved by Shakespeare derives from a 14th century scholar called Francesco Petrarca, aka Petrarch. He laid down iron rules. The rhyme scheme of the first eight lines should go ABBAABBA (e.g. “Right/ clean/mean/ light/ night/ bean/ keen/ sight”) and the last six should be CDECDE (“Old/ cool/plate/ bold/ fool/ mate.”) And the metrical stress should follow iambic pentameter (dah-dum, dah-dum, dah-dum, dah-dum, dah-dum.) Clear? Without this Italian invention, we wouldn’t have the sonnets of Milton (“When I consider how my light is spent”), Wordsworth (“Earth hath not anything to show more fair”), or Elizabeth Barrett (“How do I love thee?/ Let me count the ways.”) Shakespeare changed the rhyme scheme, but wrote 154 sonnets, entranced by a poetic form which offered conflict and resolution in a small, perfect package.

6. Gelato

Everyone knows Italian ice cream is better than any other. It’s because gelato contains 5-7 per cent fat, while most ice cream has a minimum of 10 per cent. Also, it’s churned at a slower speed than most ice cream and folds in less air ? and it’s stored and served at a temperature warmer than freezing. That’s why it’s so smooth and flavourful. But did you know the Italians invented it? The Medicis served it at their banquets, after Bernardo Buontalenti pioneered re- frigeration techniques in 1565. The ice-cream machine was invented by a Sicilian fisherman called dei Coltelli. And the appeal of the ambrosial dessert rocketed after the first mobile gelato cart (remember Chico Marx? “Get your tuttsi- fruttsi ice-a cream-a”) trundled through the streets of Varese in the 1920s.

7. Caruso

Before Pavarotti, before Boce- lli, before Gigli, the extraordinary Enrico Caruso set the template for the massive-lunged, cavern-throated, fat-but-romantic Italian operatic tenor that became a 20th-century archetype. His significance lies not just in his uniquely powerful-but-lyrical voice (he could hit top C, even late in life) but his embrace of modern recording and communication systems. One of the first classical singers to be recorded on the new phonograph, he was the first to sell 1m copies of a record ? “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci, in 1907. Through RCA Victor his appeal went transatlantic. He was leading tenor at the New York Met for 18 consecutive seasons. He appeared in newsreels, commercial movies, even an experimental film by Thomas Edison. And he remained rudely Italian: in 1906 he was fined $10 for pinching a woman’s bottom in the monkey house of Central Park Zoo.

8. Federico Fellini

Sensuous, lascivious, perverse, voluptuous, bawdy, childish and fixated by the grotesque, Fellini stands out among the great Italian directors for his embodiment of appetite. Visconti is more classical, Pasolini more brutal, Antonioni more intellectual, but it’s Fellini whose name has entered the language as an index of excess. Among the neo-realists of postwar Italian cinema, he stood out as a myth-maker. “My films aren’t autobiographical,” he said, “I’ve invented my own life for the screen.” Cinema, to him, was the realisation of fantasies. From the pathos of La Strada to the broad comedy of Amarcord, he presented life as a carnival of tragic comedy, driven by cruelty, luck and desire. He is the Italian imagination made flesh.

9. Latin

Amo, amas, amat. Amor vincit omnia. Veni, vidi, vici. Lacrimae rerum. Alea iacta est. Timor mortis conturbat me. Annus mirabilis. Annus horribilis. Lingua franca. Ne plus ultra. Post hoc ergo propter hoc. In media res. In flagrante delicta. In propria persona. In loco parentis. Infra dignitate. Sub rosa. Sub fusculum. Tempus fugit. Homo sapiens. Cave canem. Caveat emptor. Bono vox. Terra firma. Terra incognita. Ad hoc. Video. Audio. Fellatio. Whoever said Latin is a dead language is talking through his hat. Classical Latin flourished among educated folk towards the end of the Roman republic and, after Rome’s conquests of the Mediterranean, Latin became the mother-lode of romance languages, including French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian. It kept going for several more centuries as the language of international communication and science. So nil desperandum about its capacity to survive.

10. Mafia

Italy didn’t invent gangsters, but it engendered the concept of the criminal family. Groups of fraudsters, protection racketeers, smugglers and arms traffickers in certain manors or territories were called “families”; you practised omerta ? the code of silence ? about the activities of your fellow crims, and family honour meant the execution of your families’ enemies. It began in western Sicily in the 1860s, where rich landowers and merchants needed protection from bandits and bounty hunters. A century later, having moved from petty to corporate crime, it had politicians, magistrates and police forces in its grip. A 1972 film, The Godfather, introduced the world to the don, the capo di tutti capi, the consigliere, the offer that can’t be refused, the horse’s head in the bed and the concept of sleeping with the fishes. When Italians are bad, the subtext ran, they’re really inventively bad.

11. Ancient Rome

It dominated western Europe for 1,200 years, starting as a collection of settlements around the river Tiber, and growing into an empire that stretched from Britannia in the west to Egypt and Syria in the east and comprised a Greater Europe from Constantinople to Africa. It began as a kingdom, evolved into a republic for 500 years, then an empire when Julius Caesar’s heir Octavian took the name Augustus. Its 480-year imperium was a byword in autocratic rule, corruption, decadence and personal folly, until it was overrun by barbarians. But the Roman world laid down for subsequent generations the rules of how to live and was the first triumphant experiment in both domestic civilization and world domination.

12. Casanova

His name translates prosaically as “Jack Newhouse”, but Giacomo Girolamo Casanova is a byword for heartless womanizing. Neglected by his parents, he pursued careers in law, church, army, gambling and playing the violin. His main occupation, however, was playing the nobleman and having intrigues. Blasphemy, seduction, fights and scandals

landed him in prison. This reckless adventurer, lover and serial scoundrel meekly ended his days a librarian in Bohemia.

13. Dante

The “father of the Italian language” was born Durante degli Alighieri, but his nickname is enough to harrow the ears of hearers. This stern cartographer of the afterlife takes us into the furthest recesses of Heaven, Purgatory and Hell, to meet Virgil the poet and be shown where we shall all eventually be consigned. Its main significance is that he wrote it in “Italian”, or at least a blend of dialects and Latin, to prove that Latin need not be the only voice of “literature,” and that Italian could cope with epic themes. When he fell in love with Beatrice Portinari at the age of nine, fell for her “at first sight” and remained in that state, regarding her as his muse and reason for living, he invented the concept of courtly love.

14. Leonardo da Vinci

Perhaps the most diversely talented person who ever lived, Leonardo has a CV like nobody else’s. During his heyday in the late 15th century, he produced workable designs of a motor car, a tank, a helicopter, a calculator, a bobbin-winder and a machine for testing the strength of wire. He made vital discoveries in medicine, optics and hydrodynamics. He played the lyre brilliantly. He redesigned the dome of Milan cathedral. He worked for the Borgias as a military architect. And he painted a handful of astonishing masterpieces and, incidentally, the most famous portrait in the world.

15. Roberto Baggio

Known as The Divine Ponytail and feted almost as much for his satanic good looks as his magical footwork, Baggio was the finest embodiment of the golden age of Italian football in the 1990s. His speed, his agility and his ability to find impossible angles made him a legend. He appalled goalkeepers by sending shots sailing in over their heads rather than past their arms. Once, in a feat of genius, he took a corner kick and scored. It’s just as well he ballsed up the most important kick of his life ? the deciding penalty in the 1994 World Cup final against Brazil ? or we’d have had to conclude that he was superhuman.